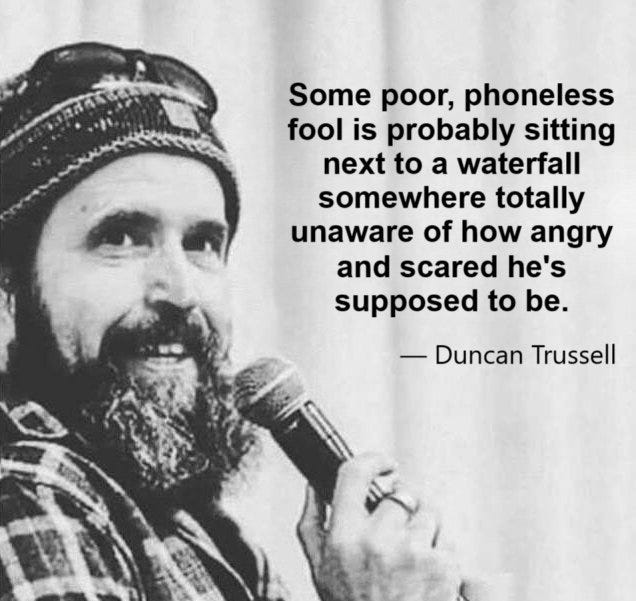

Some people don’t get it. They are not tuned in to how bad it is meant to be.

The wars, the defeat, the existential horror of life.

The decline of the nation, culture and society. The relentlessly depressing prospects for weather, the economy or relations between the sexes.

Bad news sells and we have never had so many channels with which to be told the end is nigh, our own and everyone else’s.

A tiny handful aren’t getting the message.

Most do get it, however. They are lost in a technology maze from which they cannot escape.

Fully plugged in

Many are plugged in and enjoying every minute of their programming.

Phones and other devices are ubiquitous. People are addicted to their feeds, oblivious to the drives that control them.

We often witness compulsive behaviours in public like checking phones for phantom messages or endless scrolling. Only twenty years ago these would have been considered bizarre, certainly noteworthy. Now it is normal for people to become anxious if separated from a device.

Technology seems to be everywhere.

Where I live the local council have begun erecting ugly monolithic structures with large video screens. They presumably get a cut of the advertising, but the screens also display news headlines, something I vigorously avoid.

I viewed the appearance of these things as an unwelcome intrusion. Yet others are indifferent. Garish moving images, animated advertising and visual distractions are inescapable even when outside.

When I do complain, others push back. They imagine themselves well informed and that I am uninformed. How can you not read the news? Where is the harm in a few headlines?

And yet their own news feeds are more than just a few headlines, they are like a hose. To me it looks like they are being fed like babies; spoon fed, even force fed through a digital tube.

We are drowning in information. It is impossible to make sense of it all.

So we don’t. We consume more and more in ever smaller chunks, which may be the only way to manage it.

The scale of this information overload is new which means we lack natural coping mechanisms.

Life in the past

Fifty years ago we inhabited a different world.

We were not plugged in. There were no smartphones and no internet.

Television was limited. Entertainment was more of a spectacle and a rarity, an occasional indulgence.

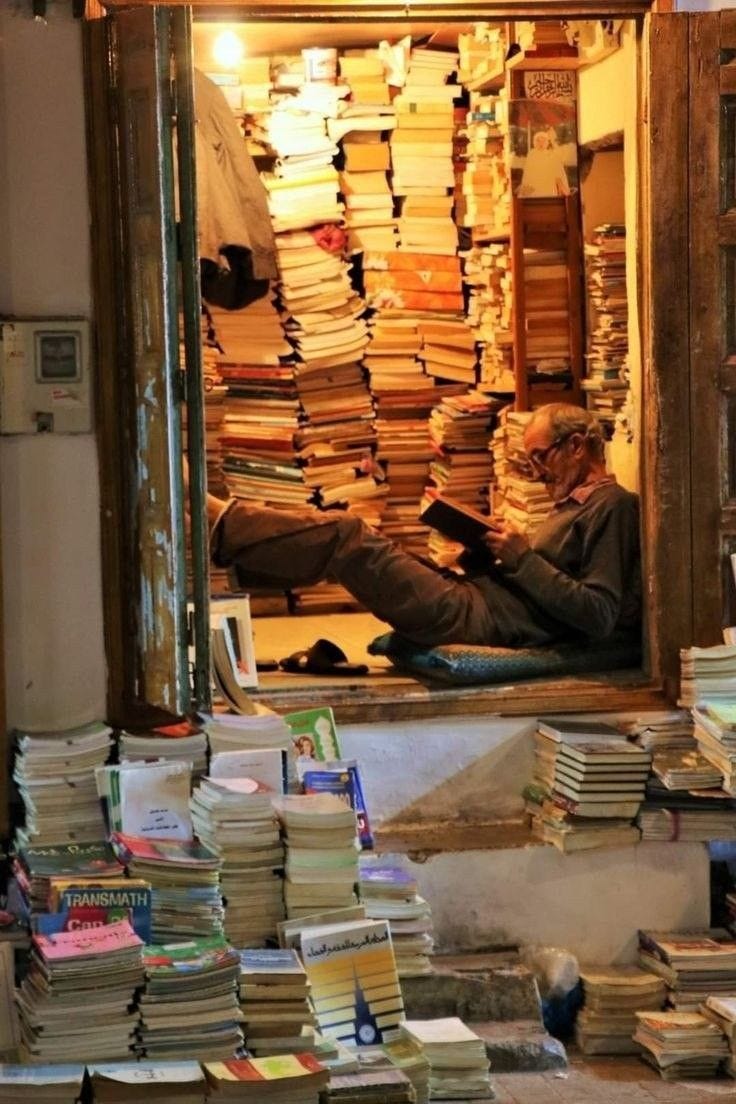

Everything was slower. People had access to less information. They had to work harder to get it. Reading longform newspaper articles and magazines. Reading books, even visiting libraries to get the books.

Was this better? We are told what we have today is an improvement. Everything on demand whenever we want it, from facts and figures to food and medicines. We can’t really say it is all bad. Much of it is impressive.

But the volume of information and the directness that comes with our amazing devices is a problem.

We cannot cope with this much content. We therefore avoid. We distract. Our attention spans then dwindle as we move away from more challenging material to distraction which by its nature will generally be easy to consume.

Content as distraction means much of the material has evolved to be compelling, to grab attention quickly.

This appears to be an inevitable decline, but is this true?

Everything now competes with the most sensational material. So even the serious stuff must use similar tactics.

This was the downfall of the broadsheet newspapers, they competed with the internet on its terms by moving online. In particular they embraced video and multimedia instead of reinforcing longer written content and related formats that many still want. The result was terminal decline. Who now buys a newspaper?

Looking back, the broadsheets had a golden opportunity to embrace that which they excelled in, the production of serious writing with impact. If anything their audiences should have grown over time as the options to read in-depth work dwindled.

This more challenging content, and the skills needed to consume it, do appear to be in decline thanks to its absence from our lives.

Deep focus

Ten years ago computer scientist Cal Newport outlined a future where the capacity to manage cognitively demanding processes would become rarer thanks to technology addiction, a skill he referred to as deep work.

His prognosis was stark. Those who lacked the ability to concentrate on difficult mental tasks would be left behind.

I remember reading this at the time and thinking Newport was overstating his case. It seemed too extreme both in the scale of the problems caused by technology use, and the degree of cognitive decline we would see. But he was clearly on to something.

People are destroying their own minds. No one is doing it to them. Subjective reports of reduced focus and low boredom thresholds are backed up by objective research on declining attention spans and inability to concentrate.

This is reflected in observational metrics of online behaviours too. Everything is getting faster, shorter and shallower to cater to changing habits.

This includes “news” which has adapted to deliver easily digestible streams of headlines at the masses, like those advertising monoliths on the streets. Many more headlines make it in to our minds even as we turn away from reading itself.

This strange paradox means ever more media narratives become lodged in our minds despite our declining focus. Because fewer people read beyond a headline any number of manufactured messages can become established, making us passive recipients of someone else’s agenda. We are told what matters and in time may lose the capacity to judge for ourselves.

That doesn’t sound like much of a life.

The prognosis is bleak. People with retarded attention spans squandering what little mental capacity they possess on media-approved ideas of what is important. A dangerous development.

In future the fullest lives may well be reserved for those who don’t indulge in these shallow activities as suggested by Newport.

Party like it is 1975

A bifurcation is happening. A fork in the road. Which route will we take? It all rests upon our willingness to put down the convenient technology and go slower but deeper. It is perhaps that simple.

Managing digital devices takes effort and we must decide how much effort we want to put in.

Living in a cabin in the woods with no electricity minimizes the effort. The choice is made for us. Being permanently plugged in requires self-control to remain sane and normal.

That balance will define most people’s lives in the decades ahead, and the majority will not make it intact. The temptations are too great. The convenience is appealing, and it is well designed too.

How many people are already using machine intelligence to write emails or read reports? I know a few who were quick to abandon these mundane tasks to technology. How capable will they be a decade from now?

We already see tomorrow’s derelicts at bus stops, train stations and shuffling along the street, unable to put their toys down. They are already lost, zombified by childish things that capture their precious attention.

I suspect the most interesting people will shun a great deal of it. They will continue to read books on paper. They will watch classic movies but probably not binge watch TV.

Social media has become a cesspit people are already abandoning, they certainly seem more embarrassed to admit they use it, so perhaps this will change too.

Others have recognized the price paid for embracing immersive technology and are rationing their use and pulling away. They are ignoring the news feeds, the celebrity drama and the fashionable wars. They are living more like we did fifty years ago.

Those who are already doing this are probably better off despite being out of the loop.

They don’t get how bad it is meant to be. The agendas aren’t reaching them. They are likely more resistant to the demoralization and the depression or anxiety it is meant to trigger.

An unplugged population like this would be healthier than we are now by avoiding the drama, the apocalyptic visions, the fear and the approved messages. Zero impact no matter how much cash they spend.

That sounds like a life worth considering. Maybe we all need a trip back to a more sensible time.

I witness first hand people using AI to respond to emails, even personal ones. Others are turning to AI for spiritual and digital love, and I've seen this also.

Staying sane with technology has become my primary challenge. Indeed, I have also faced the dilemma of "being out of the loop".

I have a high powered PC running Linux, I program in C++ and C#, but have no television. I'm currently reading George Eliot from a book printed in the 1800s. Substack is about the only social media I use. I tend now to avoid political dramas. My partner is Gen Z and collects 18th century clocks, old books and is averse to technology.

There are too few us like this but the number, at least, is increasing.

“Technology is the knack of so arranging the world that we do not experience it.”

- Rollo May